In 1970, the world was still mourning the breakup of The Beatles. The dream had ended, but the echo lingered — four men whose music had changed everything, now scattered to find their own voices again.

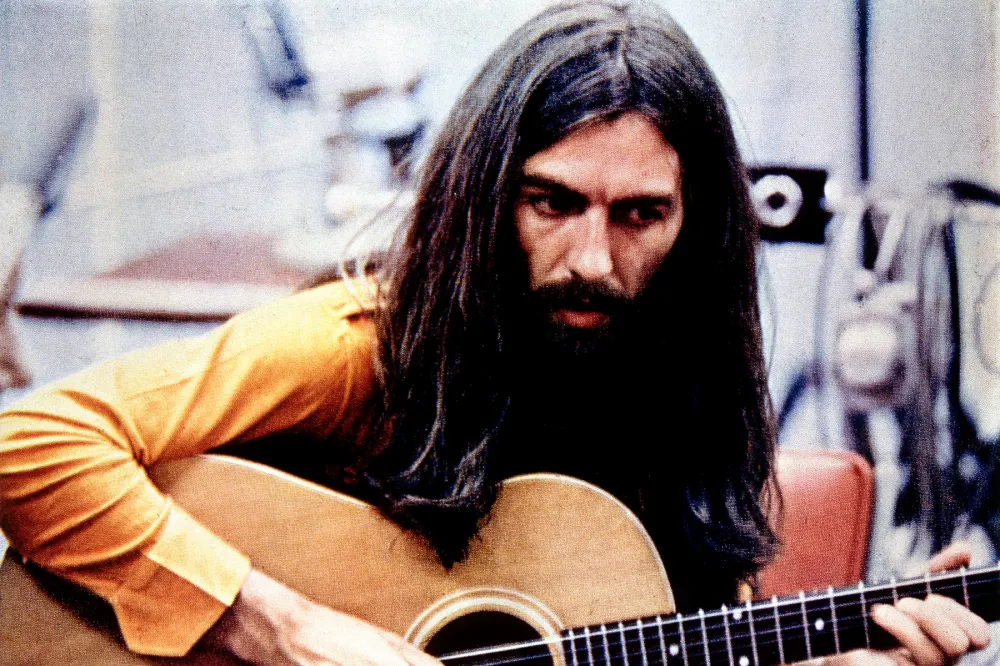

And in that silence, George Harrison, the quiet one, finally spoke. His voice came not in anger or protest, but in prayer. “My Sweet Lord” was luminous — a hymn of devotion, a bridge between East and West, between heaven and earth. It was not just a song; it was revelation.

Fans and critics alike hailed it as George’s spiritual awakening, a track that shimmered with sincerity. In its blend of gospel and Indian chant, it felt like peace itself had found a melody. But as the song climbed charts around the world, a whisper began to follow it — quiet at first, then louder, more insistent. The melody, some said, sounded too familiar.

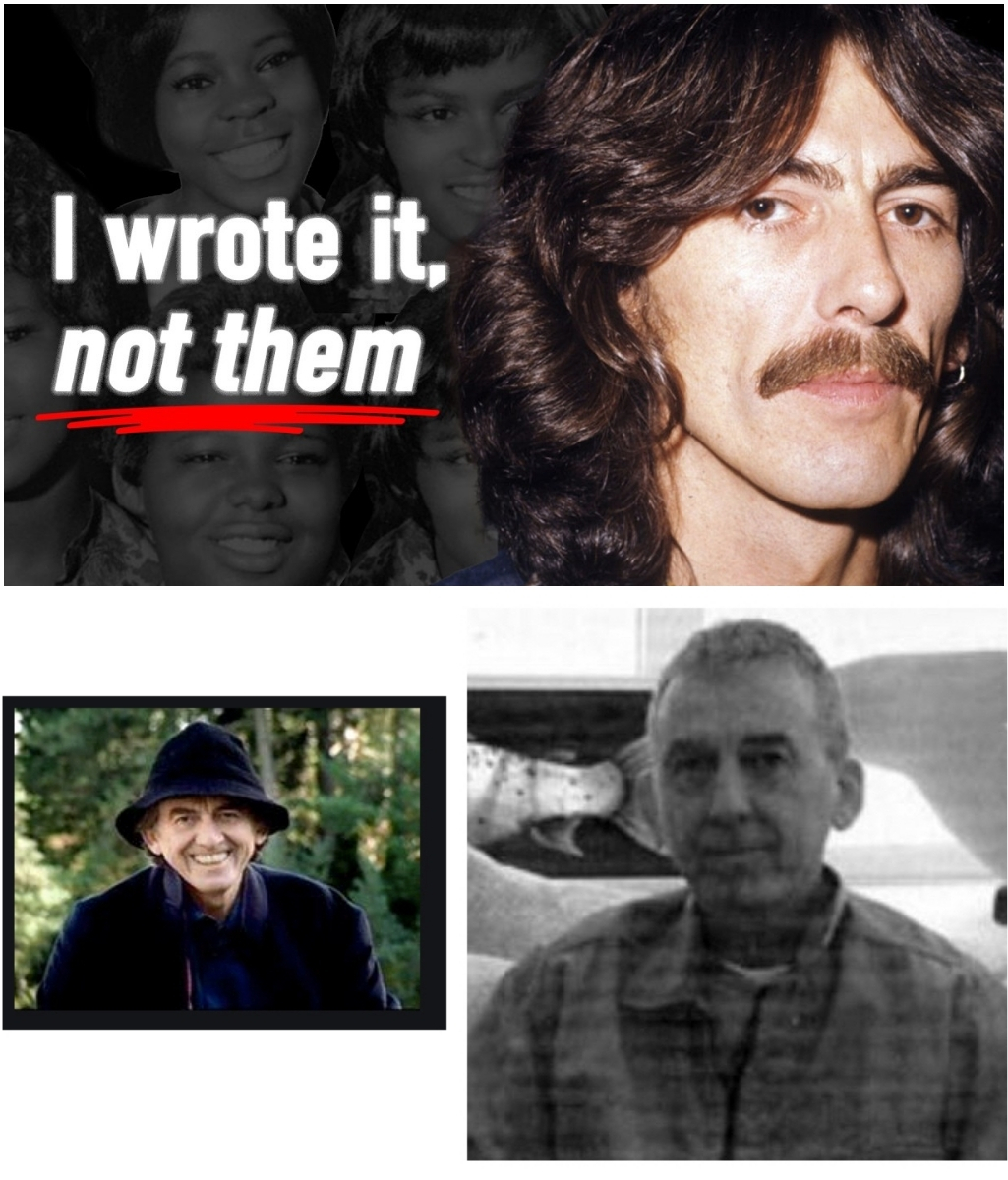

It was “He’s So Fine,” a forgotten girl group hit from 1963 by The Chiffons. The resemblance, once pointed out, was undeniable. The pure, radiant song that had reintroduced George to the world now stood accused of theft.

💬 “It was never meant to be stolen,” George said softly. “I just wanted to praise God.”

But the courts didn’t see intention, only similarity. The lawsuit stretched on for years, stripping the song of its innocence and its creator of his peace. The term “subconscious plagiarism” entered the legal lexicon — a phrase that would forever haunt Harrison’s name. For an artist who had spent his life striving for authenticity, the judgment was more than a legal defeat; it was a wound to his soul.

The betrayal deepened when it emerged that his own former manager, Allen Klein, had purchased the rights to “He’s So Fine” and pursued the case against him. What began as a misunderstanding became a cruel irony — the man who once represented him now profiting from his pain. The courtroom, filled with lawyers and reporters, felt less like a place of justice and more like a theater of heartbreak.

George handled the ordeal with characteristic restraint, but those close to him saw the toll it took. Friends recalled how he stopped speaking about the case altogether, choosing instead to pour his emotions into his next works — especially the Living in the Material World album, where spiritual longing met weary resignation. He had sought to sing of faith and freedom; instead, he was trapped in litigation and disillusionment.

In the end, George paid the price — not just financially, but spiritually. He settled the case, but the shadow never lifted completely. “My Sweet Lord” would remain a masterpiece, but a scarred one.

For the rest of his life, he carried the paradox: that a song written to praise God had been condemned by man. Yet even through the bitterness, his faith endured. He once said that every note, every lyric, was an offering — and that even flawed offerings could reach the divine.

Perhaps that is the truest legacy of “My Sweet Lord.” It was born of devotion, wounded by misunderstanding, and redeemed by time. Today, when it plays, few remember the courtroom battles. What remains is the voice of a man trying to bridge the human and the holy, whispering one final truth — even the purest song can be accused of sin, but its light still finds a way to shine.